| | 05/11/2011 Warning: new agey and lots of navel gazing |  This is sort of a followup to my blog entry on sawing straight. After I posted it I got to thinking that my approach is not really about anything other than paying attention to what you are doing, learning to "see" square, and then learning to feel when everything is going right. I'm relying on my training my body more than any specific technique or tweak. I thought about this and I think I know why I have drifted to this approach. This is sort of a followup to my blog entry on sawing straight. After I posted it I got to thinking that my approach is not really about anything other than paying attention to what you are doing, learning to "see" square, and then learning to feel when everything is going right. I'm relying on my training my body more than any specific technique or tweak. I thought about this and I think I know why I have drifted to this approach.

Many many years ago I was editing a short film and had tremendous back pain just sitting at the flatbed editor (analog editing - this was a long time ago). At the same time my posture was horrible. An actress I knew suggested that I try The Alexander Technique. While not common in the US, The Alexander Technique is pretty much a defacto training aid for singers, dancers, and most actors. It's a common course in Drama and performing Arts programs. You can learn more here.

I was desperate so I tried it. It was magic. After an initial jolt of progress it took several years but my back pain disappeared, my posture got better, etc. One premise of the Alexander Technique is that we are accustomed to use the muscles of our body (and back) to hold ourselves in bad positions and by proper training we can learn to not hold ourselves that way and do nothing instead. Doing nothing releases lots of muscle tension and lets our body behave the way it's supposed to. Over time the natural positions that are good for our body feel unnatural and a goal with Alexander is to make them feel natural again so we work our bodies more efficiently.

I realized that what I am trying to do with my woodworking is make it natural for me. I'm an amateur and I know I don't have to punch a clock on productivity. Since I have some dexterity (I can't draw or anything but I can follow a line) given enough time, and enough tools, and enough attempts I can build just about anything. But that's not the part of woodworking I am interested in.

It's like basketball. I know I can shoot baskets all afternoon and get some in. But what I want to be able to do is be able to sink baskets consistently. Craftsmanship is about certainty. So far, gosh darn it, I'm nowhere near that point.

And maybe that's what being a craftsman is. It's the ability to make something by hand in a consistent production-like manner. Whether it's a master craftsman making folding knives at so much a dozen, or a master craftsman carving gargoyles in a church, what separates the master from the beginner or the amateur is the ability to work consistently and fast. The master knife-maker may be repetitively working on a small group of unoriginal designs but he can work materials with certainty and ease. The master working high on a scaffold carving figures into stone might have more freedom in design than the knife-maker but what ties them together is the fluency with the work. An amateur - even on producing amazing stuff - simply doesn't have the practice and training to reach that fluency.

Once the fluency of the work has been mastered then for some craftsman there can be a liberation of design and an interest in pushing the envelope on what can be done. Unfortunately for most craftsman through history the opposite has been true, Henry Mayhew in the 1850's quotes a craftsman who basically states that in order to make a living there is no room for branching out. You have to be able to maintain production speed at what you know to make a living.

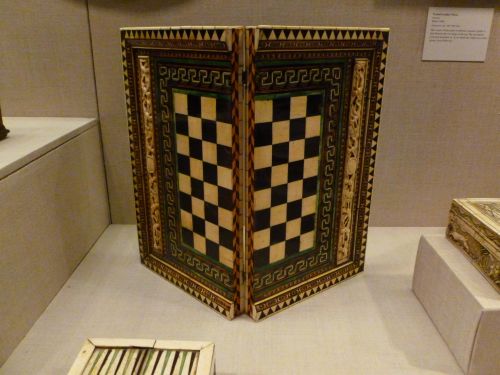

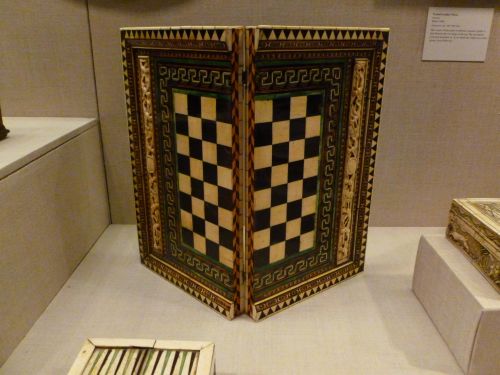

Note: The picture has little to do with anything except that it is a superb example of craftsmanship from 15th century Venice (It's in the Metropolitan Museum).

| Join the conversation | |

| The opinions expressed in this blog are those of the blog's author and guests and in no way reflect the views of Tools for Working Wood. |

|

Joel's Blog

Joel's Blog Built-It Blog

Built-It Blog Video Roundup

Video Roundup Classes & Events

Classes & Events Work Magazine

Work Magazine

This is sort of a followup to my

This is sort of a followup to my

The second thought is that I agree with much of what you say. Technique is important though, like the tricks you can learn from Frid, Schwarz, and Charelsworth about starting and controlling cuts progressing from a good knifeline to a chiseled notch for the saw, to cutting. Along those lines, I learned a really helpful trick over at WoodTreks.com from Craig Vandall Stevens. Picture a layout line for a dovetail pin or tail. If you look at the line coming up one face and around another, it looks like two lines that meet at a point at the edge of the work, forming an angle. If you place your head at the right place, the lines will appear to have no angle and will appear to be one straight line. Try making your cut with your head at that position. It's magic. I put lines at two crazy angles and tried and the cut worked. But, maybe it's just concentration, as you say!

I find this sentence puzzling: "An amateur - even producing amazing stuff - simply doesn't have the practice or training to reach that fluency." Other than output rates, why does "fluency" matter? If "fluency" is defined as unlocking freedoms and capabilities to achieve what an amateur never could, I suppose it would make some sense, but your sentence posits that the amateur is "making amazing stuff." Isn't the quality of the stuff what matters, and not how fast the maker got there?

"Isn't the quality of the stuff what matters, and not how fast the maker got there?"

Not if you are too slow to make a living at it or for an amateur take so long you lose interest. Supposing it takes me 1/2 day (4 hours) to make a proper quality dovetailed drawer. and it takes a master only 1 hour. I either charge 4 times as much or earn one quarter the amount. Neither option is viable long term. Therefore unless I get faster I will not get the opportunity to do the project in the first place.

For an amateur some people love perfection and that makes them happy, others just want to get stuff done because the end work is more important. It varies from person to person.

”I’ve never made furniture professionally,” he told Oscar Fitzgerald in an interview in 2004. “I’m an amateur and always will be. That’s the way I want to die. I’m an amateur by nature. David Pye wrote somewhere that the best work of this century would certainly be done by amateurs.”

1. Being sure and certain that one can construct whatever is required

2. Being able to handle, with surety and certainty, all the tools involved in a project.

3. Being able handle all the sub-skills involved - such as sharpening one's tools.

Is the "old" man of 70 (I'm almost there) going to saw as fast as the 20 something? Probably not. Can he/she still be a master? Of course.

In other terms, with practice, review and improvement, the tool in the hand becomes part of the body and so the principle of proprioception applies to it too. (You get to the stage of unconscious competence). So getting the body right is a precondition for getting the work right.