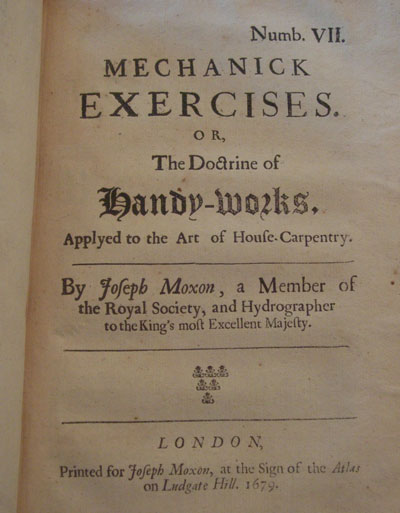

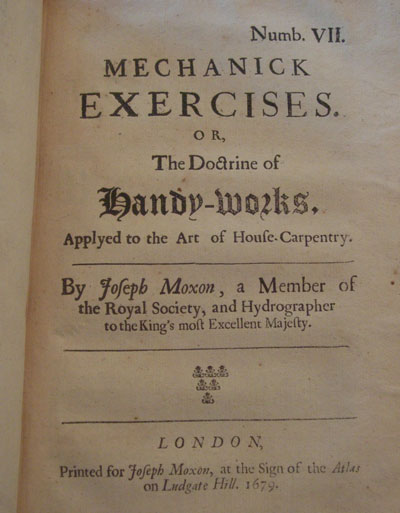

The first book written in English about woodworking was Joseph Moxon's Mechanick Exercises. Originally serialized from 1677-1683 (and continued on other subjects for the next decade or so) it is widely regarded as a major landmark in printing and technology and is still available. But both these modern books are taken from the 1703 edition, which was published posthumously and was itself a reprint of the original landmark text. The first book written in English about woodworking was Joseph Moxon's Mechanick Exercises. Originally serialized from 1677-1683 (and continued on other subjects for the next decade or so) it is widely regarded as a major landmark in printing and technology and is still available. But both these modern books are taken from the 1703 edition, which was published posthumously and was itself a reprint of the original landmark text.

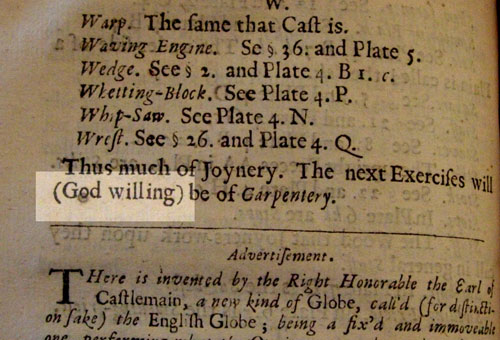

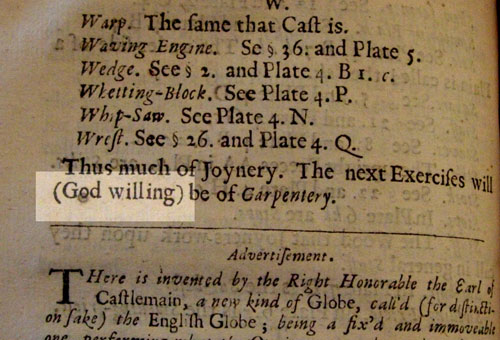

The differences between the 1703 edition and the 1677-83 edition are minor but telling. In the later edition the type is slightly smaller, the advertisements for Moxon's globe business have been removed, more modern spellings of words are used - "Joynery" in the original becomes "Joinery" in the reprint, the pagination is different etc. However one minor change speaks volumes. You see we take "how to books" for granted. For the past couple hundred years at least publishers have understood that there is a market for "how to" books and stuff on every subject has been published, republished, and is readily available. This wasn't always the case. In the 1703 edition the chapter on joinery ends with a note:

"Thus much of Joinery. The next Exercises will be of Carpentry."

Straight and to the point. Even unnecessary because, after all, the next exercises on carpentry begin on the next page.

In the 1678 edition (when the section on joinery was originally printed), the section on carpentry wasn't due out for a year yet, and certainly wasn't printed or maybe even written when the joinery section appeared. And this is what I find so poignant and telling: The chapter on joinery ends with slightly different wording:

"Thus much of Joynery. The next Exercises will (God willing ) be of Carpentry."

No other chapter ends this way. You see in 1678-'79 the project was cutting edge. Was this parenthetical remark because the project was so hard to do? Was it because it wasn't as financially successful as hoped? Did not enough rich people in England see the point of spending money on a subject matter normally confined to workmen of a lower class? Was the concept of a subscription, first introduced in England with this project, too unfamiliar to get enough subscribers? Did Moxon bite off too much and wasn't sure if the next chapter would ever appear? Was the political climate and the economy to unsteady to warrant further risk? (the "Popish Plot" upheaval begins 1678). I don't know, but I can certainly feel a human touch I find nowhere else in the book. The human sense of frailty that happens when you plow new ground, introduce new ideas, and new ways of doing things. I feel kinship with Moxon, This year a lot of our projects have been delayed as we work on new designs and figure out new ways of manufacture. I happy to report that Moxon did persevere. The next chapter on carpentry was completed as was succeeding chapters, and today we can take his monumental leap forward in publishing, and "How to Writing" for granted.

One closing thought: do yourself a favor. Have an adventure. Try something new. Maybe a style of woodworking you never did before, or a project that seems a little too hard at the moment, or maybe a technique that you have only read about previously. One closing thought: do yourself a favor. Have an adventure. Try something new. Maybe a style of woodworking you never did before, or a project that seems a little too hard at the moment, or maybe a technique that you have only read about previously.

(The second photograph is of the original 1679 cover of installment on carpentry).

|

Joel's Blog

Joel's Blog Built-It Blog

Built-It Blog Video Roundup

Video Roundup Classes & Events

Classes & Events Work Magazine

Work Magazine

The first book written in English about woodworking was Joseph Moxon's Mechanick Exercises. Originally serialized from 1677-1683 (and continued on other subjects for the next decade or so) it is widely regarded as a major landmark in printing and technology

The first book written in English about woodworking was Joseph Moxon's Mechanick Exercises. Originally serialized from 1677-1683 (and continued on other subjects for the next decade or so) it is widely regarded as a major landmark in printing and technology  One closing thought: do yourself a favor. Have an adventure. Try something new. Maybe a style of woodworking you never did before, or a project that seems a little too hard at the moment, or maybe a technique that you have only read about previously.

One closing thought: do yourself a favor. Have an adventure. Try something new. Maybe a style of woodworking you never did before, or a project that seems a little too hard at the moment, or maybe a technique that you have only read about previously.

When the prevailing climate cleared and they could return, they continued in this line of work. In time, the family business branched out and Joseph left to start up his own printing/publishing business with a focus on cartography, hydrography, the making of various scientific instruments and of course, getting admitted to the Royal Society.

During the time period when Joseph Moxon wrote the initial serial issues of Mechanick Exercises/Handy-Works, he was still involved with the Puritan sect, only just beginning to claim a reputation as a man of science (an unheard of step for a tradesman). It's not surprising to me that he included what was a fairly standard salutation in this early edition. He was, if nothing else, a man of discernment when it came to how to manipulate and politic his way around religious, political and academic circles.

My thesis is that his upbringing, the move to Holland, the stance against the Church, his battle to be admitted to the Society all paint the picture of a rebel, an early social reformer who sought to do things his way all the while working to bend the rules of the Powers That Be to fit his wants and needs.

By 1703, the role of the scientist was rising in social and political power. It's not surprising that, given the societal shifts of attention from the purely religious to the scientific, that a reprint of Mechanick Exercises would read as more modern and less a tribute to the religious side of life.

There is additional information from Moxon's writings that at one point, he had not sold enough subscriptions and threatened to simply burn the entire lot of issues rather than pursue the series any further. Luckily for us, he gained the backing of some very important people, such as Hooke, and Pepys and succeeded in his endeavors.

It's a standard phrase but he didn't use it elsewhere else in a closing salutation of any other chapters - which is my point. Something was going on in 1678 that made him a little more worried than usual. in 1678 stuff was happening. The Popish plot was a source of much upheaval and in May 1679 Pepys was arrested for treason. Might have been that. You mention that he was concerned at one point that subscriptions weren't selling. Any idea what year that was? I can make a pretty good educated guess that the sections on smithing were better subscribed than the section on woodworking because my edition is made up of edition two of the first two sections of the smithing section but the first edition of section three onward which suggests leftover pages of the first edition starting with section 3.

Incidentally by 1679 Moxon was already a member of the Royal Society (see 1679 frontispiece above) so the idea that he was a religious outsider at this time makes no sense. The spelling was corrected in the third 1703 edition because by that time an older spelling would have looked odd. Spelling and printing and literacy was progressing by leaps and bounds at that time.

The Royal Society was quite willing to ride both sides of the saddle (Hooke was vocal on this matter). Many members subscribed to proper religious beliefs in order not to run afoul of the prevailing church of the time which would have seriously jeopardized their financial backing (a generalization on my part).

Moxon was brought up as a social activist, engaged in publishing bibles and tracts supporting an outlawed religion. He apparently had little problem with going against the prevailing order, a stance which may have stood him in good stead as he became more and more involved with the Society.

For spelling, the page titles had been corrected to read "Joinery" but the name for the tool remained "Joynter". We don't know for sure who set the type for the 1703 edition but we don know that even in the earlier editions, there was some variation throughout the chapters (even in the volume on Printing) in spelling. People continued to spell according to how something sounded, along with spelling according to the developing rules of the literary community. Even in the 1703 edition you see some variation in spelling.

Moxon was the author, printer and publisher. Was he also the typesetter? We don't know. The variations indicate that once set, it was too expensive or time consuming to go back and reset a page to make a correction that in all likelihood no one would notice or complain about. The vagaries of reading and spelling in the 18th century were such that if it sounded right, it worked.

Moxon was also exposing trade secrets that had been jealously protected by the various Guilds. Not being a member of any Guild, and given his proclivities to espouse a new order of society, he joined ranks with the intelligentsia in supporting the role of the Philosopher (or all around scientific type) during the ascendance of the Society.

There is also the problem of the bookbinder, who (as I have learned) may have been nearly illiterate. All of which means we really don't know who set the type, who arranged the signatures and who bound the copies. What we do know that is that there is a huge amount of variation in pagination throughout both volumes of Mechanick Exercises, but that was often the case in 17th and early 18th C books.

On your other points. Once a page was set it would have been printed and the type redistributed. Stuff gets corrected only going forward. The later chapters of the first edition mentions errors in engravings and in the text which were corrected by the second edition. As for the variation in pagination the only problems I have seen are when different editions are bound together.

Moxon wasn't revealing any secrets that anyone cared about. After the great fire of London [1666], there was such a shortage of craftsman to rebuild, any vestiges of guild restrictions on woodworkers were unenforceable and the guilds increasingly became social organizations. Power in the crafts slowly drifted to the trade unions who were mostly interested in wages - and were not able to restrict trade.

I think, based on my evidence and yours, you should take Moxon's remark at face value. In 1678 here was a guy at the cutting edge of information technology and he wasn't so confident that the project would continue to completion.