|

|

11/09/2010 |

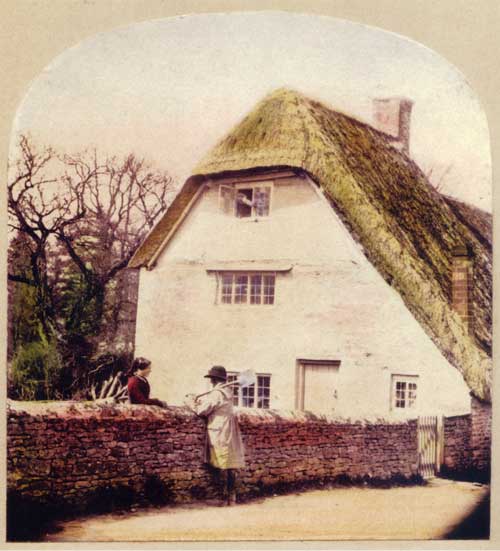

In the early 1850's T. R. Williams took a trip to a small village in Oxfordshire for the purpose of photographing a country lifestyle that was fast disappearing. Photography had only just been invented in 1839 and this project reflected technical challenges similar to someone today photographing Mount Everest in IMAX 3D. In the early 1850's T. R. Williams took a trip to a small village in Oxfordshire for the purpose of photographing a country lifestyle that was fast disappearing. Photography had only just been invented in 1839 and this project reflected technical challenges similar to someone today photographing Mount Everest in IMAX 3D.

The finished series, called "Scenes from Our Village" was published in England in 1856 and was part of the popular entertainment of viewing 3D pictures, a popular pastime up to the early 20th century. The pictures disappeared from common view only to turn up occasionally in car boot sales and old pictures auction.

Brian May, The former guitarist from Queen has had a lifelong interest in stereo photography and the history of its development. He began collecting stereo images in general and images from this series in particular when he was at university. Continued interest in this series of pictures resulted in a new luscious book "A Village Lost and Found" by May and Elena Vidal which reprints the original series and includes background history, various versions of the pictures, and additional information to help us get a handle on the camera technology of the time, and details about the village and the people in the pictures. A stereo viewer is also included.

The reason I am writing about the book is not because I am a Queen fan (although I am), not because I like stereo photography (although I am and own and use tons of stereo cameras, projectors and accessories) but because it's rare that we get to see actual pictures of daily life from so early in time. While by 1856 the industrial revolution was well under way and in places like London a recognizable consumer society was forming, the small village was still pretty much as it had been for centuries. This is probably why Williams went back in the first place, to create a nostalgic look at the village as a memento for people who grew up in places like this only to move as adults to big expanding urban industrial cites. The reason I am writing about the book is not because I am a Queen fan (although I am), not because I like stereo photography (although I am and own and use tons of stereo cameras, projectors and accessories) but because it's rare that we get to see actual pictures of daily life from so early in time. While by 1856 the industrial revolution was well under way and in places like London a recognizable consumer society was forming, the small village was still pretty much as it had been for centuries. This is probably why Williams went back in the first place, to create a nostalgic look at the village as a memento for people who grew up in places like this only to move as adults to big expanding urban industrial cites.

The painterly, hand colored pictures, of these nostalgic village scenes remind me of the illustrations done by Beatrix Potter for her children's books, although instead of Flopsy, Mopsy, and Cottontail we get actual people. What struck me about the pictures is how beautiful the wooden thatch cottages are and how elegant the curved lines on the wagons were. Take a look and try to appreciate the craft that went into building everything. Just look at the lines of the thatch, wonderful flowing curves and elegant proportions. The wagons don't have a single straight line in them, they look organic, blend with the countryside and don't have a sharp angles of later industrial technology. And this is what's important from a woodworking standpoint. If you work with a skilled hand complex angles, gentle curves, subtle sculpting is pretty easy. However once you add in machine setups angles and shapes become regular, it's much harder to eyeball a gentle curve with a router jig than it is with a drawknife. Look how a shingled roof closely hugs the underling rafters and the hand laid thatch is packed and trimmed to graceful shapes full of personality. The painterly, hand colored pictures, of these nostalgic village scenes remind me of the illustrations done by Beatrix Potter for her children's books, although instead of Flopsy, Mopsy, and Cottontail we get actual people. What struck me about the pictures is how beautiful the wooden thatch cottages are and how elegant the curved lines on the wagons were. Take a look and try to appreciate the craft that went into building everything. Just look at the lines of the thatch, wonderful flowing curves and elegant proportions. The wagons don't have a single straight line in them, they look organic, blend with the countryside and don't have a sharp angles of later industrial technology. And this is what's important from a woodworking standpoint. If you work with a skilled hand complex angles, gentle curves, subtle sculpting is pretty easy. However once you add in machine setups angles and shapes become regular, it's much harder to eyeball a gentle curve with a router jig than it is with a drawknife. Look how a shingled roof closely hugs the underling rafters and the hand laid thatch is packed and trimmed to graceful shapes full of personality.

I'm really enjoying the book, it's well written, very well researched, and I am having fun taking a leisurely stroll in 3D through the village. I'm going to take a closer look at the pictures, because for all that the pictures are staged there is lots to be learned here about rural life in the 19th century. But that will take many enjoyable hours and I look forward to it. We don't stock the book but you can easily buy it from all major booksellers.

Note: the pictures here are only single images of pairs of stereo images in the book. The book also includes a rather ingenious folding 3d viewer.

|

Join the conversation |

|

Joel's Blog

Joel's Blog Built-It Blog

Built-It Blog Video Roundup

Video Roundup Classes & Events

Classes & Events Work Magazine

Work Magazine

In the early 1850's T. R. Williams took a trip to a small village in Oxfordshire for the purpose of photographing a country lifestyle that was fast disappearing. Photography had only just been invented in 1839 and this project reflected technical challenges similar to someone today photographing Mount Everest in IMAX 3D.

In the early 1850's T. R. Williams took a trip to a small village in Oxfordshire for the purpose of photographing a country lifestyle that was fast disappearing. Photography had only just been invented in 1839 and this project reflected technical challenges similar to someone today photographing Mount Everest in IMAX 3D. The reason I am writing about the book is not because I am a Queen fan (although I am), not because I like stereo photography (although I am and own and use tons of stereo cameras, projectors and accessories) but because it's rare that we get to see actual pictures of daily life from so early in time. While by 1856 the industrial revolution was well under way and in places like London a recognizable consumer society was forming, the small village was still pretty much as it had been for centuries. This is probably why Williams went back in the first place, to create a nostalgic look at the village as a memento for people who grew up in places like this only to move as adults to big expanding urban industrial cites.

The reason I am writing about the book is not because I am a Queen fan (although I am), not because I like stereo photography (although I am and own and use tons of stereo cameras, projectors and accessories) but because it's rare that we get to see actual pictures of daily life from so early in time. While by 1856 the industrial revolution was well under way and in places like London a recognizable consumer society was forming, the small village was still pretty much as it had been for centuries. This is probably why Williams went back in the first place, to create a nostalgic look at the village as a memento for people who grew up in places like this only to move as adults to big expanding urban industrial cites.  The painterly, hand colored pictures, of these nostalgic village scenes remind me of the illustrations done by Beatrix Potter for her children's books, although instead of Flopsy, Mopsy, and Cottontail we get actual people. What struck me about the pictures is how beautiful the wooden thatch cottages are and how elegant the curved lines on the wagons were. Take a look and try to appreciate the craft that went into building everything. Just look at the lines of the thatch, wonderful flowing curves and elegant proportions. The wagons don't have a single straight line in them, they look organic, blend with the countryside and don't have a sharp angles of later industrial technology. And this is what's important from a woodworking standpoint. If you work with a skilled hand complex angles, gentle curves, subtle sculpting is pretty easy. However once you add in machine setups angles and shapes become regular, it's much harder to eyeball a gentle curve with a router jig than it is with a drawknife. Look how a shingled roof closely hugs the underling rafters and the hand laid thatch is packed and trimmed to graceful shapes full of personality.

The painterly, hand colored pictures, of these nostalgic village scenes remind me of the illustrations done by Beatrix Potter for her children's books, although instead of Flopsy, Mopsy, and Cottontail we get actual people. What struck me about the pictures is how beautiful the wooden thatch cottages are and how elegant the curved lines on the wagons were. Take a look and try to appreciate the craft that went into building everything. Just look at the lines of the thatch, wonderful flowing curves and elegant proportions. The wagons don't have a single straight line in them, they look organic, blend with the countryside and don't have a sharp angles of later industrial technology. And this is what's important from a woodworking standpoint. If you work with a skilled hand complex angles, gentle curves, subtle sculpting is pretty easy. However once you add in machine setups angles and shapes become regular, it's much harder to eyeball a gentle curve with a router jig than it is with a drawknife. Look how a shingled roof closely hugs the underling rafters and the hand laid thatch is packed and trimmed to graceful shapes full of personality.

Re: Humans and organic shapes. I think that yes we appreciate them but as a whole we gravitate toward order, pattern and proportion. We love the straight line, we love the right angle. This is not to say we don't equally love the curve but I think the straight and the right angle is easier for us to make and therefore we connect more to it. I understand your point about spokeshave vs a fence on a tablesaw but look at way earlier cultures and even they tried to make things straight and square. Curves are more for flourishes, straights are more for the heavy construction of something.

Even the paintings of Jackson Pollock are done within a rectangle.

Thanks for the tip on the book Joel.

Cheers,

Andy

Lawrence