|

|

11/16/2010 |

It's not unusual if you read the National Geographic, or watch documentaries about aboriginal tribes in various places to discover that anthropologists have observed that the natives were discovered to be using old steel axes and machetes that they must have gotten from traders a long time ago. It's not unusual if you read the National Geographic, or watch documentaries about aboriginal tribes in various places to discover that anthropologists have observed that the natives were discovered to be using old steel axes and machetes that they must have gotten from traders a long time ago.

This is true, catalog evidence shows how the English edge tool industries went a long way to provide customized tools for specialized crops and lumber work all over the world

The earliest price list extant that refers to the famous Smith's Key of 1816 is a printed price list of tools and prices from C. 1821 - 1841 that contains notations in Spanish. The current thought of researchers is that the price list (which survived without an accompanying set of illustrations) was used by some traveling salesman to take orders from customers in South America or some other Spanish speaking region. For example "Plantation Hoes" are listed in 9 different styles ranging from North American ("Carolina", "Virginia") to South America ("Barbadoes","Brazil"). A "Brazil" style axehead is also listed.

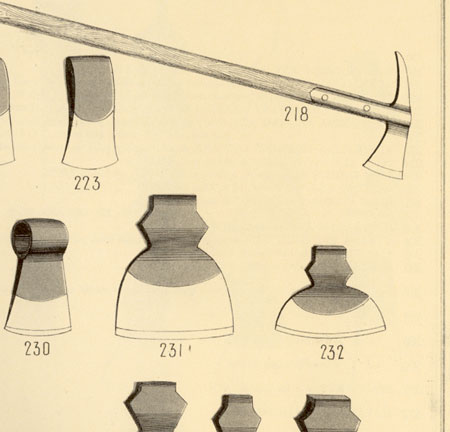

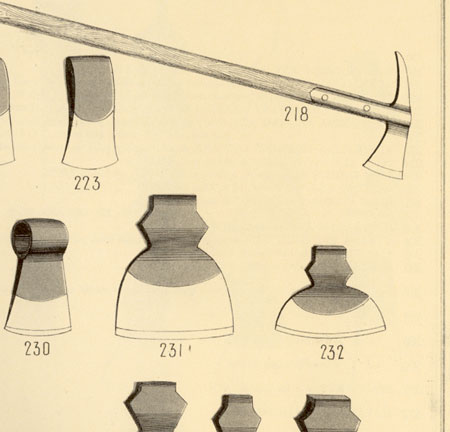

In the C. 1860's Elwell catalog of edge tools (photo above) pages and pages of similar yet slightly different edge tools are shown. You have the "Montevidean Axe", the "Columbia" and "Guatemala" axes. The list goes on.

English edge tool makers were happy to execute specific regional designs for anywhere in the world they could trade. Most of these tools were destined for the plantations and ranches of the colonies and former colonies world wide. The "Honduras or Mahogany Squaring Axe" (shown above #231) seems much like a regular western broad axe but bigger, I suppose to be more useful in milling the giant Mahogany trees that were harvested under horrific conditions in South American lumber camps.

Chances are, and I am speculating here, is that an importer would travel up and down the countryside taking orders from local retailer. These folks had specific requirements of the tools they needed. So when the order was placed, by a letter sent by boat to England, notes and sketches would be added for special modifications.

One advantage of having craftsman forge out shapes by hand is that, even in the context of production work in a factory setting, customize parts were easy to make. Of course once made the new item would find its way into the catalog of the company.

|

Join the conversation |

|

Joel's Blog

Joel's Blog Built-It Blog

Built-It Blog Video Roundup

Video Roundup Classes & Events

Classes & Events Work Magazine

Work Magazine

It's not unusual if you read the National Geographic, or watch documentaries about aboriginal tribes in various places to discover that anthropologists have observed that the natives were discovered to be using old steel axes and machetes that they must have gotten from traders a long time ago.

It's not unusual if you read the National Geographic, or watch documentaries about aboriginal tribes in various places to discover that anthropologists have observed that the natives were discovered to be using old steel axes and machetes that they must have gotten from traders a long time ago.

The notation is in old Spanish and I believe all of those words are from the Old World. I think it was used in Spain.

Stephen

Thanks for the link! I have copies of both 18th century builder's dictionaries and price guides but Salmon seems a combo of both with lots of information not covered in other texts.

I don't know of any 19th century source that suggests that basic tools were provided by a carpentry/joinery master (except for an apprentice). I don't know of any 18th century source which discusses this either way. However, certainly wholesaling happened all the time to retailers. Also in the case of many unskilled jobs (or semi-skilled jobs) or jobs with a captive labor force (slaves, indentured servants, plantation workers, miners, etc) it was very very common for for works owners to give tools to their "employees" and charge them accordingly by a payroll deduction. So there would have been a call for larger quantities. Also it is possible and I would have to check Salmon more closely, that he simply lifted his pricing and quantities from wholesale lists and didn't bother to find out individual retail prices. Most surviving prices from the 18th and early 19th century are wholesale lists as there was no retail mail order.

Palladio Londonensis is an interesting book. A local bookseller has a copy which, while I can't afford it, is certainly a pleasure to browse through. I'll have to go back and review the section on pricing.