|

|

12/27/2017 |

I own just about every hand tool every invented. My mentor, the late Maurice Fraser, used to say that in the old days you could borrow something from the next bench, but nowadays most woodworkers are on their own. If they don't own the tool, they won't be able to do an operation.

There is truth to this philosophy, but for beginners the idea that you first need to acquire a store's worth of tools before you can do anything is both misleading and discouraging.

When I need to cut a groove, I reach for one of my many plow planes (actually a Stanley 45 - no need to sharpen any of the others). But I was taught a perfectly good method, that is still very applicable for stopped grooves, and pretty fast for anyone who happens not to collect tools like I do.

The most common use for a groove I can think of is holding a panel in a frame and panel construction. Nobody sees the bottom of the groove, which is makes it easier. As long as the groove is at least as deep as needed to hold the panel, the bottom finish isn't critical. On the other hand, usually at least one edge of the groove will be visible next to the panel and unless it is clean, it will truly look awful.

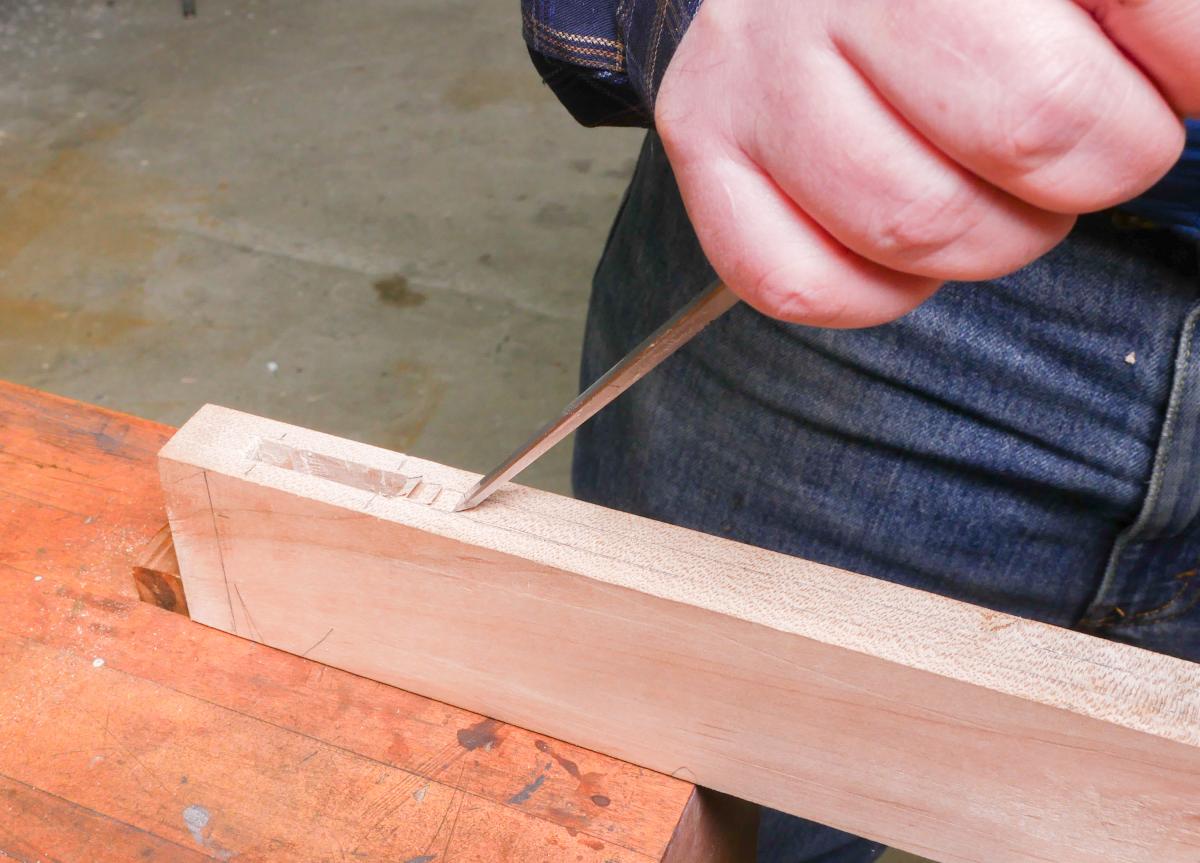

How do I cut a groove without the plow plane? The first step is setting my mortise/combination gauge to slightly larger than the chisel I plan to cut the groove with. It just has to be a touch larger, and since panels are typically angled, you have a lot of leeway with width. I want a little extra width so that I can pare to a clean line (like I did on my mortise). With the combination gauge set, scribe the groove the length of the frame. In this case, I have centered the groove and stopped both ends. With this method, stopping is easy and it saves having to worry about an unsightly gap or plug at the end of the piece. I've also run a pencil line in the scribe lines so that I can see what I am doing.

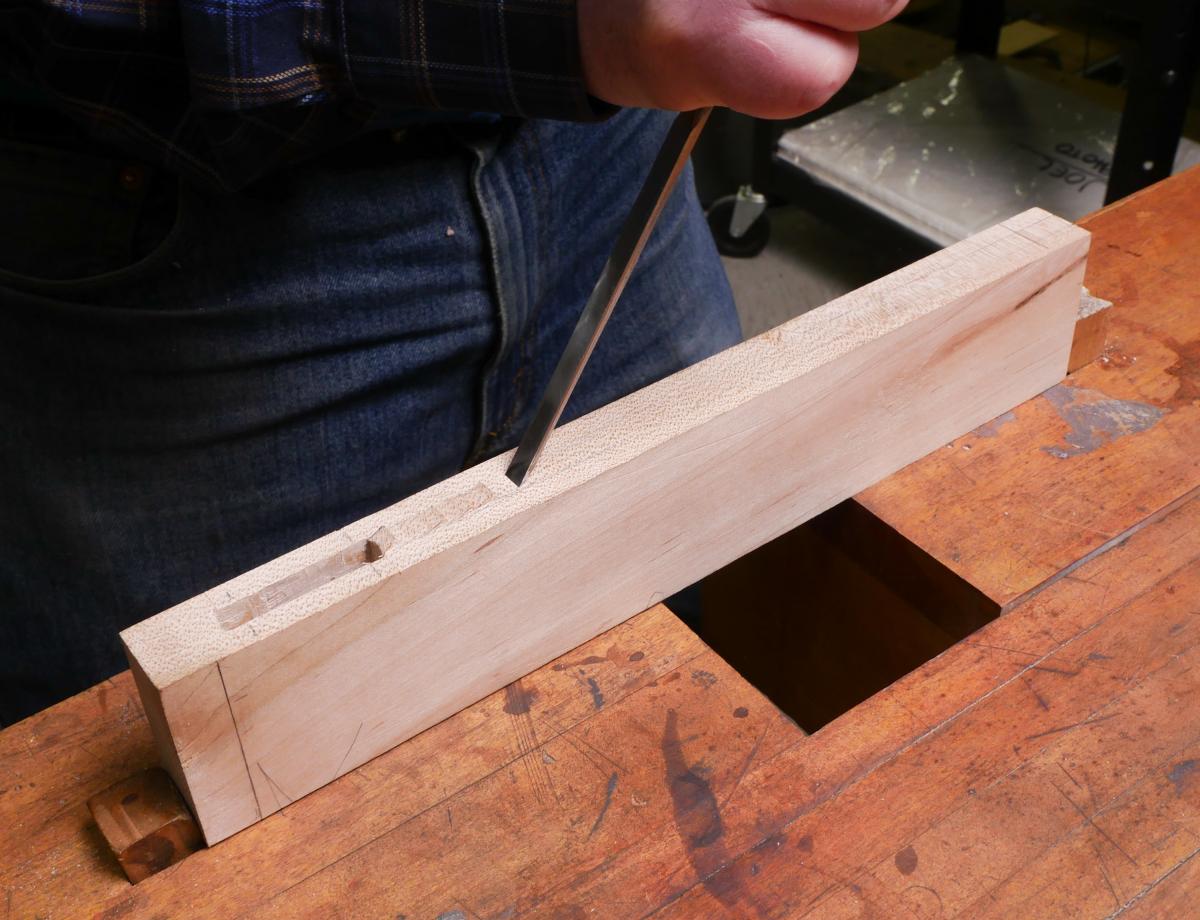

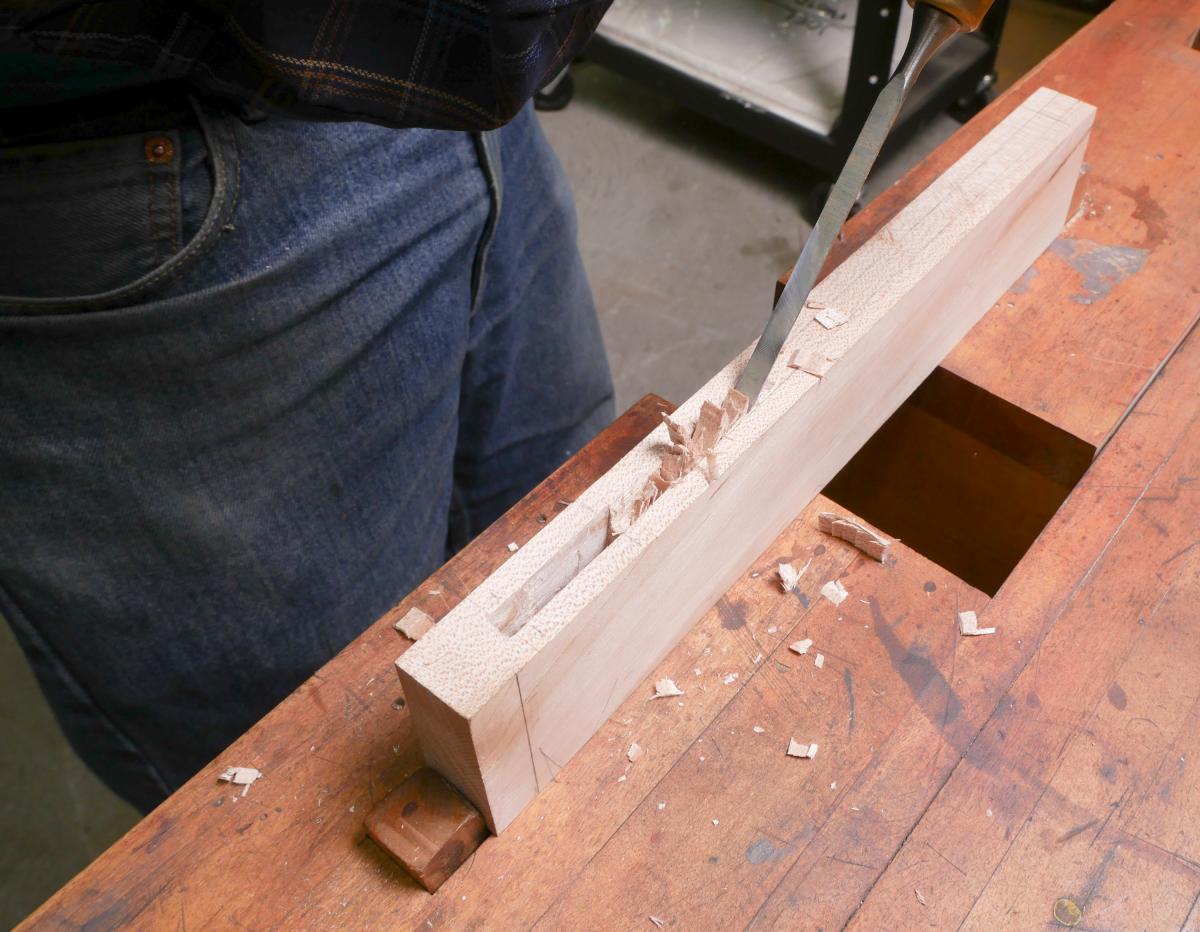

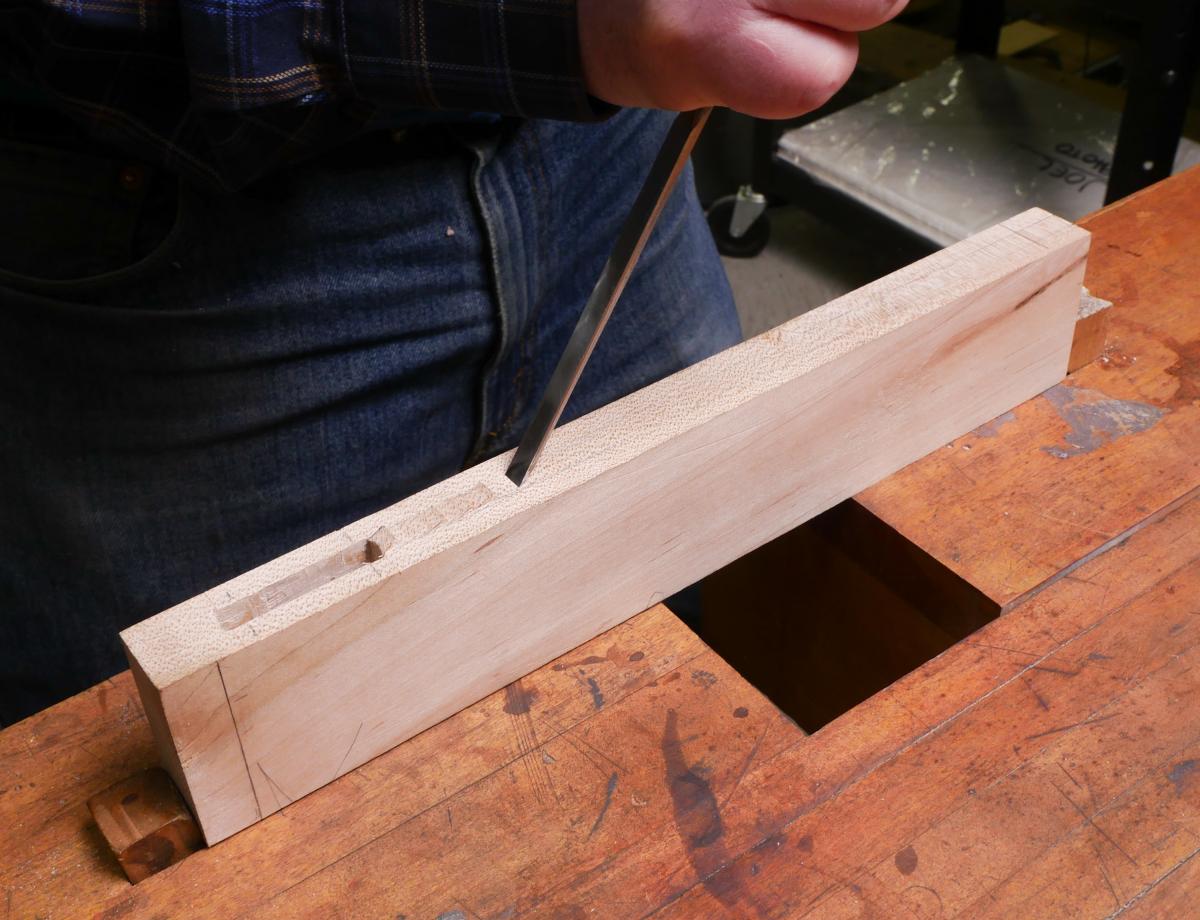

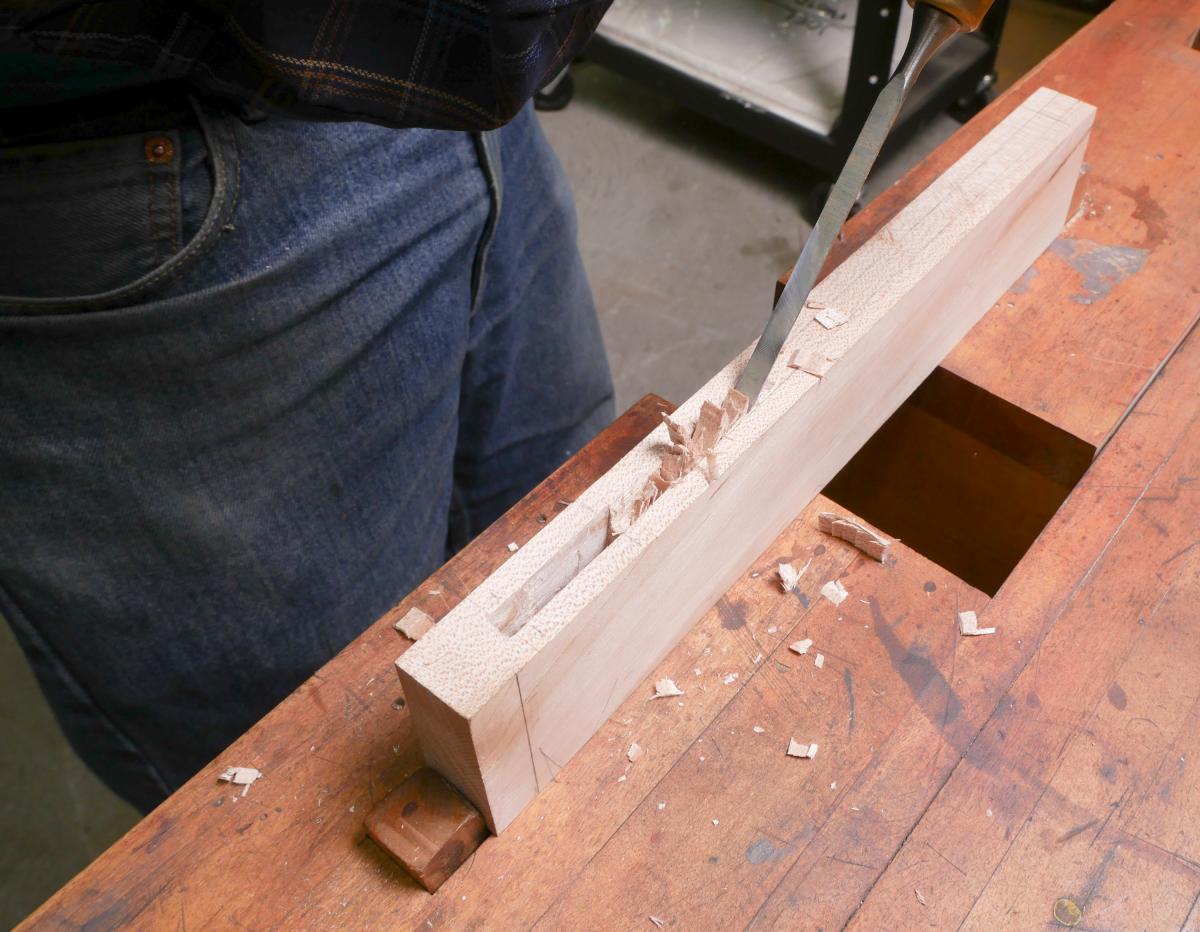

In a nutshell, here is how to make the groove: Using a regular 1/4" bench chisel I am going to make a series of chisel cuts, none particularly deep, each lifting up a bit of wood. Then, as I do multiple passes, I can easily clear the chips I have raised, and then repeat the procedure to go deeper. I have a tendency to do work in sections as I go in steady progression along the board.

I have found that periodically reversing the chisel and chopping at partially removed chisels helps clear the waste, as does using the chisel parallel to the groove to also break up and clear chips. I have gotten into the habit of using a different narrow or even slightly wider chisels (to chisel parallel to the grooves) to break up waste. I do this primarily because normally I would have to do two rails and two stiles to complete a frame and it saves wear and tear on the main chisel I need. I don't have to stop and sharpen.

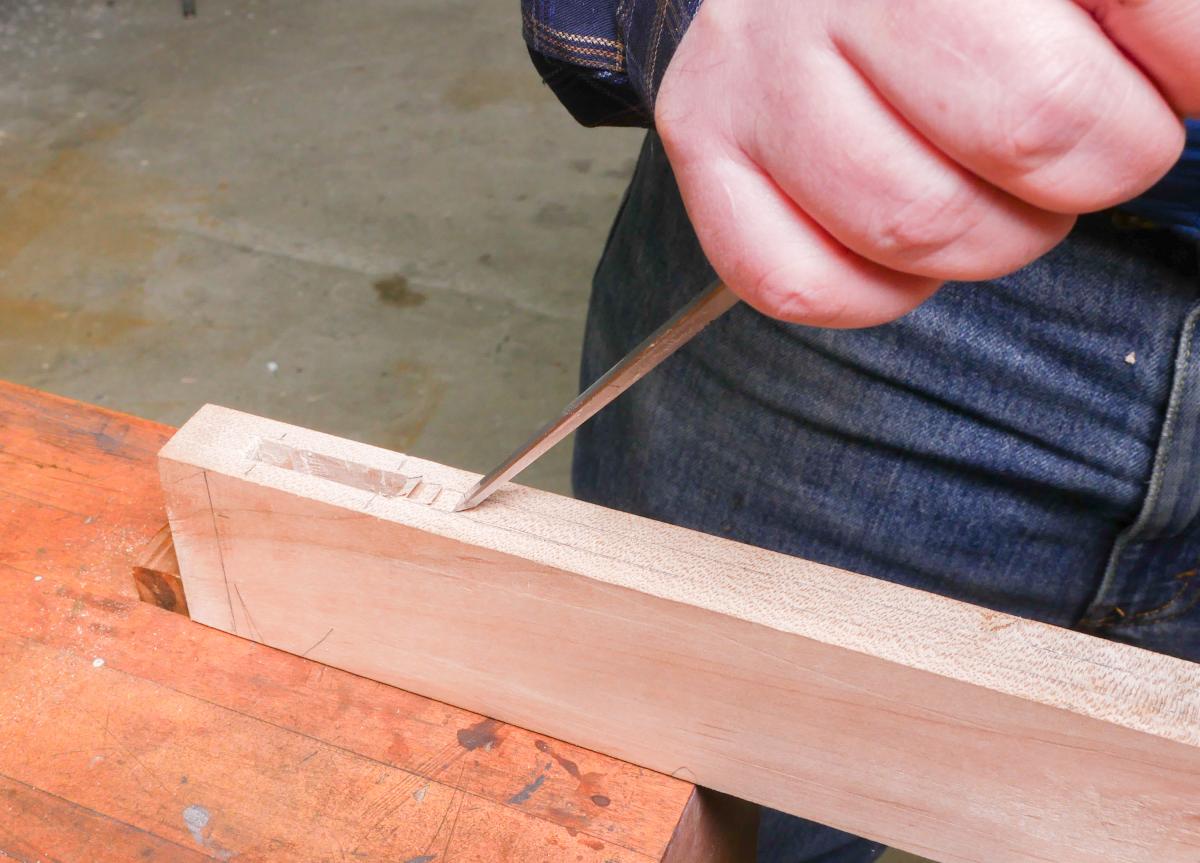

When I am done to depth I take a paring chisel - the widest I have available - and slice down at the scribe lines to give me a finished clean edge.

Your first reaction to this method might be that this is a really slow way of doing it. Compared to a plow plane, absolutely. This stile took me about 20 minutes. I could go a faster if I wasn't trying to take pictures, but not much. If you are doing a stopped groove like this and you have a plow plane it might make sense to use this method for the first inch or so at each end of the groove, and then plow the rest. Unless you have a router table, for one small box bottom it might be faster and safer to do the gooves by hand than trying to jig up a router for the grooves.

|

Join the conversation |

|

Joel's Blog

Joel's Blog Built-It Blog

Built-It Blog Video Roundup

Video Roundup Classes & Events

Classes & Events Work Magazine

Work Magazine

Thanks for hand tool education (and history). Now that I'm retired I've been focused on learning and building on my hand tool skills and find the experience to be a lot more fun and satisfying. It's also real good on the Wow factor when friends ask "How you do that".

Keep smiling,

Dan

If you are doing a stopped groove like this and you have a plow plane it might make sense to use this method for the first inch or so at each end of the groove, and then plow the rest.

I think you just plane it to fit. It means figuring out what material has to go, then with a bench plane planing selectively and checking as you plane that you are removing material in the right spot. The big danger is if the grain on the wood goes the wrong way, in which case you can either shift around the orientation of the piece, find a new piece, or just plane carefully with a sharp iron the best you can. Of course depending on if it's paint grade or not you might have some leeway with the fit - or not.

For a fairly long workpiece like the one you show, I've used one little trick to speed up the process a bit. Since I generally have my plow plane set up already (to plow matching grooves in matching workpieces), I will take two or three stopped passes down the workpiece--beginning just before one end and stopping before I get to the other end. If I deepen the cut just a little with each pass, I can establish a shallow but clear groove to guide the chisel. The main advantage is that it saves me the trouble of setting up my mortise gauge, and I can be certain that the grooves will all line up exactly.