|

|

11/15/2017 |

In February 2010 I wrote a three-part blog entry showing that the earliest illustrations and texts about the planes we call "mitre planes" were in the marquetry sections of various books. My theory was that these planes were most likely used for leveling and planing the surfaces of marquetry panels and materials. The exotic woods used in marquetry are sometimes very hard and can easily tear up the soles of any wooden plane. You can read part one of my blog here, part two is here, and finally part three.

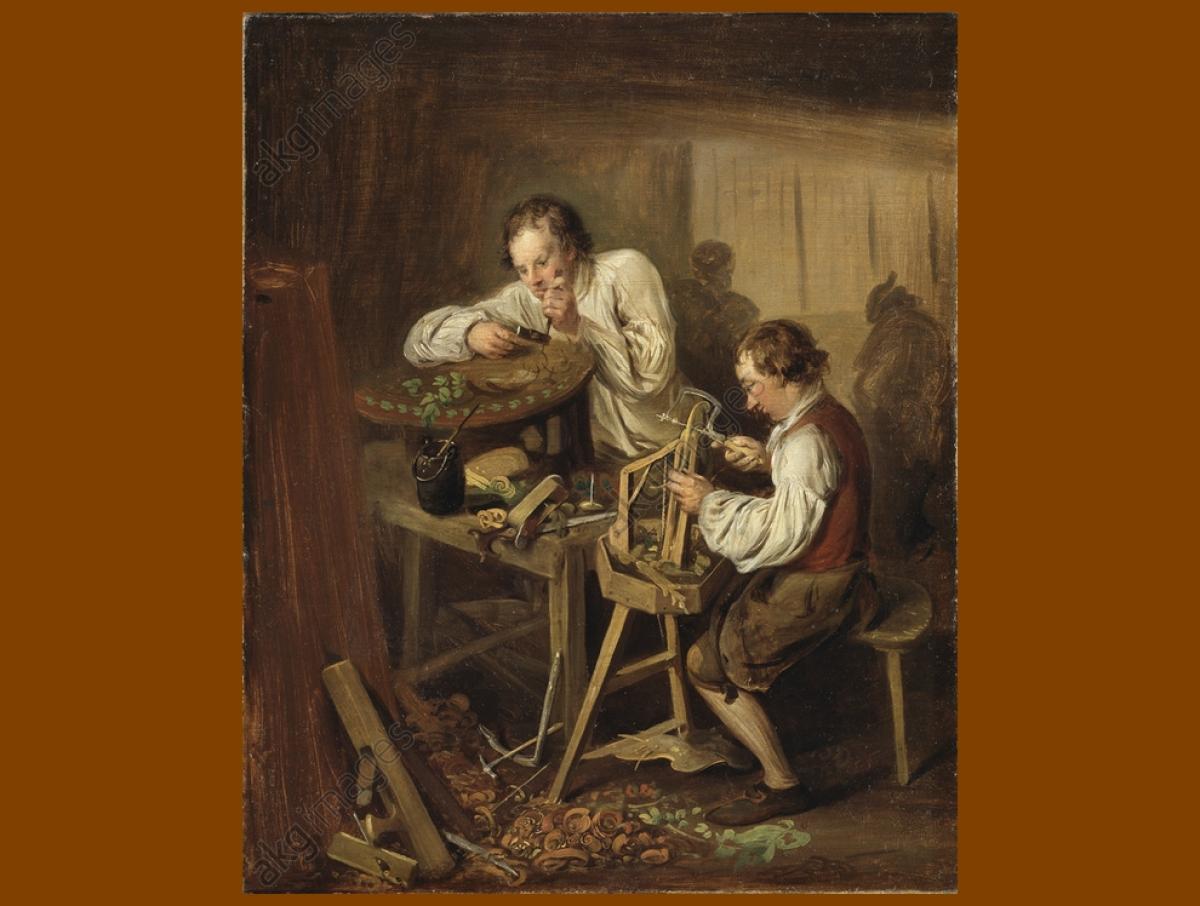

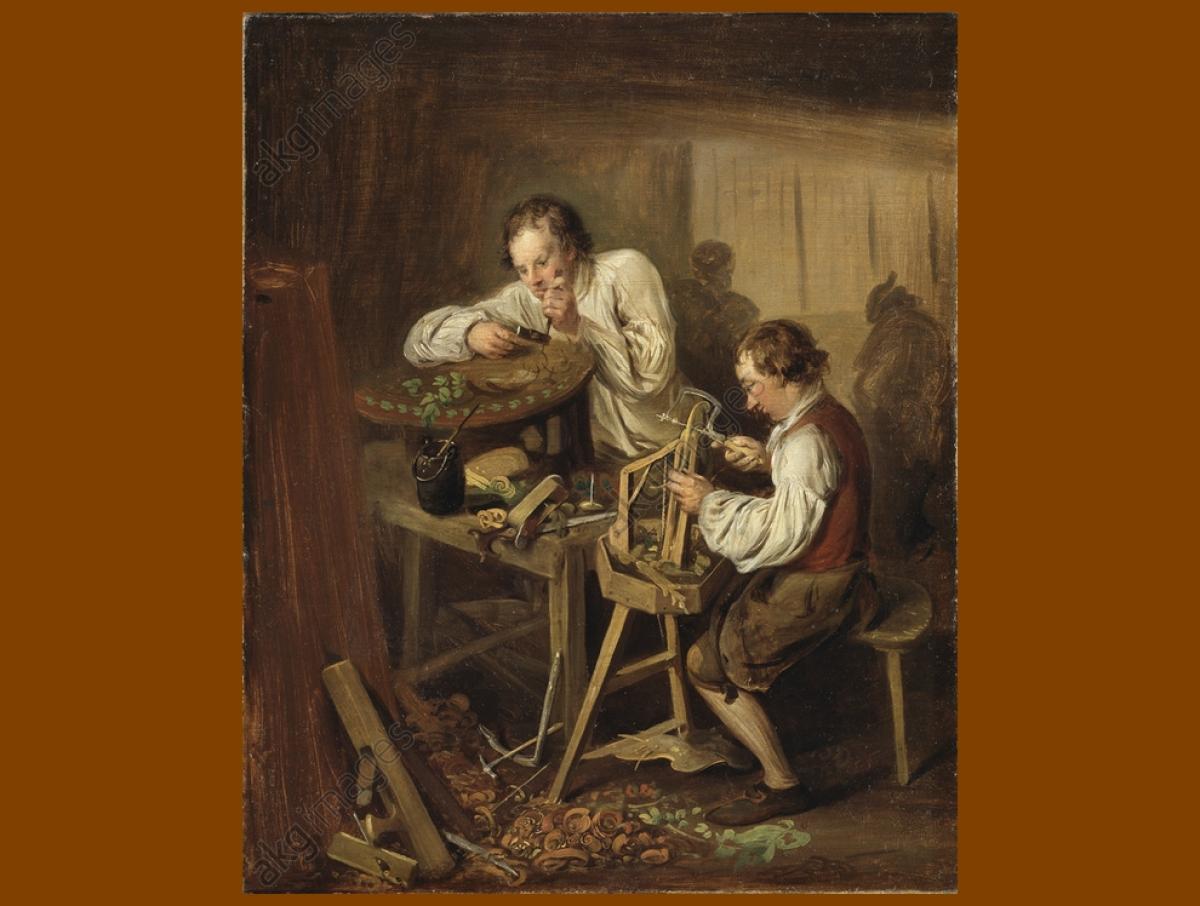

David Lundqvist, a woodworker who lives in Sweden, just sent me a "missing link" in support of my thinking. The painting above, called "Die Ebenisten" [The Marqueters], was painted by Elias Martin in England between 1768-80. The painting shows two marquetry journeymen, George Haupt and Christopher Fürloh (anglicised as Furlong), working for John Linell in London. I'll talk in a moment about why two Swedish journeyman were in London, but first focus your eyes on the metal plane located pretty much in the middle of the painting.

I think this is the earliest contemporary image of what we now call a mitre plane in England, and it comes just before the period when plane makers such as Gabriel and Moon were entering the metal plane market. The plane itself doesn't look dovetailed and seems to follow the European technique of brazing the body to the sole; admittedly the scan I have isn't perfectly clear, so I am not positive about this. David's research on Swedish cabinet makers led him to this painting. David also found two contemporary citations of the phrase "Rabot du Ebêniste," or "Marqueter's plane" -- not "plane of iron," the term that the few earlier references in marquetry tool pages use for these planes, nor "mitre plane," a later term that shows up around 1820. We finally have both visual proof and documentation that the plane was recognized as a marquetry plane, not a mitre plane. Well done, David!!!

Another interesting question is why two Swedish marquetry journeyman were in England in the first place. My assumption was that England at the time was starting its rapid economic expansion with the advent of the Empire and the Industrial Revolution. The country was growing in wealth and an attendant demand for European-trained craftsman to create fancy furniture for the country's nouveau riche. David took a different approach in answering this question. David observed that by the middle of the eighteenth century the closed guild system of crafts, which was still thriving in Continental Europe, was starting to vanish in England. The craft guilds - groups of master craftsman in England - still certified new masters and still gave a seal of approval, but no longer had the power, legal or otherwise, to restrict trade. They were mostly social societies for the richer craft classes. Anyone could be a cabinetmaker, and a cabinetmaker could set up shop and hire apprentices. The loosening of the guild restrictions allowed new ideas to mature, which attracted talented immigrants. New blood and ideas became established in England, along with employment and training for immigrants. Trained Swedish craftsman could find good work and advancement in England, and not have to fight to get guild permission back home.

The painting currently hangs in the National Museum in Stockholm.

|

Join the conversation |

|

Joel's Blog

Joel's Blog Built-It Blog

Built-It Blog Video Roundup

Video Roundup Classes & Events

Classes & Events Work Magazine

Work Magazine

Very interesting stuff. I went back and read your earlier post - also very interesting. I've never really understood what the mitre plane was for, but your posts make a lot of sense. When I first looked at it I assumed the plane body was made of wood with a metal sole - a hybrid of the two designs, but in your text you talk about it being all metal. Do you think there is a chance it could have a wood body? The tones of the body seem to match the tones of the other wooden planes in the picture as well as the marquetry horse that is being used? Although having said that there does appear to be a slight tone difference between the front 'bun' and the sides. Previously you mentioned that problems can exist with an all-wood bevel-up low-angle plane because of distortion, or even breakage, of the sole. Adding a metal sole might be the solution they came up to solve those problems? It would seem an obvious solution.

Metal soled wooden "mitre" planes existed. Roubo shows them in his marquetry book (which we stock) and I have a poorly made one in my collection. The problem is that the wood moves and the metal sole doesn't. Roubo is writing about the same time as the painting in the blog, and it's a transitional time. The English were busy introducing inexpensive strips of iron that meant that by 1780 or 90 building a dovetailed "mitre" plane wasn't a big deal anymore, and the results far exceed what you can do with a wood body and metal sole. Roubo in this context anyway is illustrating the last of the older technology, not the first of the new.

Thanks for publishing this photo. I'm really enjoying looking over the period tools, miter plane included. That foot-powered clamp is especially fascinating. If I had the space, I think I'd build one for myself.

Many thanks for your great blogs. May I correct you in a couple of areas? I first published this painting in my book Paintings in Wood: French marquetry furniture, 2001.

The identity of the two workers is unclear, as well as the workshop depicted. Elias Martin came to London in the 1770s and Georg Haupt left London in July 1769, aged 27.

At present, the Elias Martin painting is very informative for tools and materials (please note the colourful green veneer and the use of the knife to inlay the marquetry), but it does not help for portraying famous makers.

With regard to the mitre plane. You make some interesting proposals and offer great ideas. In my opinion, and according to Roubo, mitre plane is not specifically for marquetry and certainly not to finish a marquetry surface. In my 20 years + of making marquetry, I have used a mitre plane only once on my marquetry panel: it was simply a disaster with all the different wood grain direction and various density. The most appropriate plane to finish marquetry, as illustrated and explained by Roubo, is the toothing plane. The toothing plane does not get a lot of credit but is it the most useful plane I have in my workshop, for finishing marquetry and difficult timbers. I may have 7 or 8, all different size, all ready to go. As a conservator of 18th century antiques, I can also confirm that toothing plane marks are very common on 18th century furniture.

The name mitre plane in Roubo French is interesting and telling well its function: varlope-onglets. Strictly translated as Jack plane (varlope) for mitre (onglets / angles). Mitre plane in English is pretty close to the French 18th century name, and self explanatory: for mitres (and therefore end grain).

My mitre plane is very useful when cutting small parquetry pieces, straight lines in veneer. But certainly not for finishing the marquetry.

An article on toothing plane would be great. I see they are revived by big tools companies, they are great.

Continue the great blogs,

Best,

Yannick

Thanks for your email. Unfortunately I do not own a copy of your book so I didn't know about the painting prior to David's email to me. The identity and information on the painting comes from David who did original research. I don't know how he reached his conclusions but I think it is based on primary sources. I will forward your email to him, and see if he has any comments.

A good mitre plane should be able to plane with essentially no tear-out in any direction. Cast mitre planes don't work nearly as well as steel soled ones. Most of the old ones that are now are available are worn out so your experience cannot be extrapolated to every mitre plane (especially when new) and I own several counter examples. Not to mention the plane is identified as a marquetry plane. Roubo, writing about the same time as this painting, wonders why the iron plane he describes aren't used more generally. Even on a good day iron planes were not common. They were expensive. Nowhere do I suggest that these iron marquetry planes were the only way of leveling a freshly glued up panel, or even planing this exotic veneers faces before sawing the pattern. There is always more than one way to skin a cat. What I can say with certainty is that the iron soled plane made it's first printed appearance in lists of marquetry tools long before it was known as a "mitre plane".

When I first saw the painting I thought it was of a craftsman and an apprentice.

As somebody who was an apprentice carpenter and joiner, from almost 60 years ago when hand tools were normal and somebody who has studied art the painting appeals greatly to me. However, a painting is not a photograph and often a painter would make sketches, from the scene, take it back to his studio and design a painting which he probably wanted to sell.The end result may not reflect the actual scene as it was. He may well move things around, take things out, put things, which were not there, in and not portray things accurately.

As for tools, woodworkers were not well off and would often make their own planes with the blacksmith making the iron and who would be making these metal planes in London at that time?

One of my ancestors, who was a carpenter, moved to London in the 1700's when there was a lot of building going on in London and one reason was because of the aftermath of The Great Fire of London of 1660 and also because London was becoming very fashionable.

Joel, this is nice. Please keep posting your thoughts.